By: Jeffrey Staso

Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash

Self-directed learning is when you take ownership of the information presented to you. Learning is much more effective when you are actively involved in the process of creating meaning (Settles, 2012). Students find learning is much more effective when they take ownership of the information they are learning (Deslauriers et al., 2019). When you understand why you are learning something and how it relates to your overall goal you are much more likely to retain the information.

I want to be careful to point out that self-directed learning does not necessarily mean you will be learning on your own. However, even with an instructor, students need to have a high level of self-direction to succeed in an online learning environment (Shapley, 2000). Making yourself an integral part of creating meaning is just as important when you are in a classroom setting. Even the best instructor cannot make you learn something. Instead, a good instructor will help you answer the questions necessary to keep your motivation high and help you create meaning from learning.

History of Self-Directed Learning

Self-directed learning has been around as a concept for a long time. It has roots in Vygotsky and Constructivism (Crow, 2015). There have been many learning theories and instructional models that have attempted to create a unified theory.

Candy’s Four-Dimensional Model (1991) concluded that self-directed Learning had the following dimensions:

- Motivation as a personal attribute

- Self-direction as personal attributes

- The ability to control the organization of learning

- The ability to learn outside of the classroom

Garrison’s Three-Dimensional Model (1997) narrowed this to three dimensions:

- Self-management

- Self-monitoring

- Motivation

Brocket and Hiemstra’s Personal Responsibility Orientation Model (PRO) (2011):

- A process in which a learner assumes responsibility for all aspects of learning (p.24)

- A goal that focuses on a learner’s desire to learn (p.24)

How do you Start Self-Directed Learning?

Photo by Matt Duncan on Unsplash

As you can see, all of these models focus on internal motivation to succeed and the ability to take control of the learning process. Simplified, they break down to the following:

- Motivation

- Planning

Self-Directed Learning: Motivation

Self-motivation is crucial for taking ownership of learning. Increasing and improving student motivation has been a topic of instructional design for decades. Williams & Williams (2011) say “Motivation is probably the most important factor that educators can target in order to improve learning.” When you take control of your own motivation for learning, you are well on your way to a quality education.

Intrinsic Motivation – The drive to accomplish a goal based on internal reasons such as curiosity.

Extrinsic Motivation – A drive to succeed due to external rewards such as grades, increased salary, etc.

The best way to motivate yourself is to continuously remind yourself of the reason you are undertaking a course of study. Sometimes it is easy to forget the purpose of your efforts when things get difficult.

Self-Directed Learning: Planning

Much of your course of study will be determined by the instructor via learning objectives. However, it is still up to you to understand why you are studying what you are studying.

Ask yourself these questions about learning:

- What do I want to learn?

- Why do I want to learn it?

- Why is this important?

- How will this knowledge be used?

Identify What you Need to Learn and Why

Getting started in self-directed learning can be confusing because there are many different kinds of topics you may be learning. To better understand the types of learning you might encounter, let’s take a look at a common learning module called Bloom’s Taxonomy. In short, this model attempts to organize the types of learning into categories (Forehand, 2010). First, Bloom breaks up learning into three broad domains:

The Cognitive Domain deals with understanding and applying mental processes. This is the most commonly cited domain for education.

The Affective Domain deals with receiving and responding to emotional processes. For example, dealing with anger and grief or empathically helping others with their emotions.

The Psychomotor Domain deals with perceiving and responding to physical processes. This domain is used when discussing how best to learn the physical aspects of sports, how to tie a knot, or use a certain tool like a wrench or a drill press.

Cognitive Domain Processes

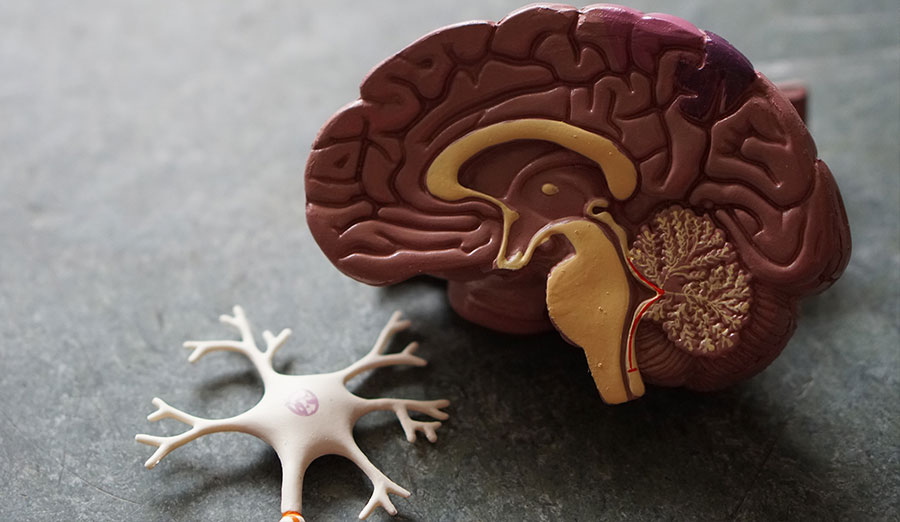

Photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

If you are engaged in learning something in the cognitive domain you are learning something mental. This might be how to start a business, how to build a web page, how to model a car, or how to debug a computer. Some of these tasks will also include physical applications, but let’s keep it simple.

In Bloom’s Taxonomy the domains are further broken up into processes (Forehand, 2010). The model was revised in 2001 to feature the following processes:

- Remember – Storing facts in your brain for easy retrieval

- Understand – Demonstrate comprehension of complex topics

- Apply – Use information or skills to accomplish a task

- Analyze – Read data and determine a course of action

- Evaluate – Make judgments based on elements

- Create – Put items or ideas together to create something new

Learning Objectives

Using these processes, instructors break up topics into small measurable chunks called learning objectives. These objectives are invaluable as a guide to see what you will be learning. Later on, they also work as a way to self-evaluate if you’ve learned what you needed to from a course. Learning objectives utilize processes to stay focused on the important aspect of the topic.

Example Objectives

- Remember: Student will be able to list five basic HTML tags

- Understand: Student will be able to choose the most correct medical billing code for a given diagnosis

- Apply: Student will be able to successfully install a given operating system on a new computer

- Analyze: Students will be able to identify potential markets from a list of sales trends

- Evaluate: Student will be able to suggest allocation of funds given a sample quarterly budget

- Create: Student will be able to create a 3D model of a kitchen using a given software program

Check your course syllabus for learning objectives. Work with your instructor to determine what you will be learning in an online course. If you are unclear on an objective, ask your instructor for clarification.

Why am I learning this?

By identifying why you are learning something you’ll have the motivation to take ownership of the information. Each of these processes is a potential answer to the question “Why am I learning this?”

Remember: I need to know how much to bill for this service

Understand: I need to know how to enter information into Microsoft Excel

Apply: I need to take this list of expenses and create a budget for this business

Analyze: I need to decide what the company could do to lower costs

Create: I need to come up with some ideas for new services that will expand my business

Work with your instructor to determine why a topic is necessary. Don’t be afraid to ask how something fits into the bigger picture. Once you fully understand why you are learning a new topic and what kind of topic it is, you are ready for the next step.

How to Learn

Self-directed learning models tend to focus mainly on getting a learner to the topic, but not how to best learn something. For that, we’ll need to look somewhere else.

Schema Theory

When my daughter was little, she didn’t know the difference between dogs and cats. She would point at an animal, any animal at all, and say “kitty”. It didn’t matter if it was a cat, a dog, or a cow. As she got older she was able to identify traits that made it easier to determine what classification of animal she was looking at. A kitty with long legs and a mane became a “horsey”. Jean Piaget called these classifications schemas (Flavell, 1996).

As we learn more about a topic we create more specialized schemas that allow us to quickly identify information. We also can group schemas into “packets”. These packets allow us to store information for easier retrieval from memory. For example, learning to drive a stick shift can be difficult at first. You will need to construct schemas for how to use the gear shift, how to use the clutch, etc. As you become more confident these schemas merge to become one easily retrievable packet of information.

Imagine these schemas in your brain like subway stations. Some topics are big stations with lots of different subway cars going to other stations. Some of them may be small stations that are tucked away and hard to get to. When you start visiting (or thinking) about some of the smaller stations your brain starts building more subway tunnels to them. The more you think about it, the stronger (and more direct) the path to get there will become.

Connecting With Your Experiences

Photo by Josh Riemer on Unsplash

Try to connect new information to larger topics you already know something about. The more you learn about a topic, the more you visit it, the more you think about it, the easier it will be to grow your knowledge (Zull, 2004). Therefore, the best way to connect new knowledge with old experiences is through reflection and purposeful practice.

Reflection

Self-reflection has long been thought to be an important step in cementing knowledge. Lew & Schmidt (2011) found that keeping a self-reflection journal and responding to a given prompt had a positive (albeit slight) impact on student grades. The important thing when reflecting is to actively connect what you learned to your own experiences.

Ask yourself these questions:

- What does this remind me of?

- What stands out to me?

- How does this relate to other things I’ve learned in this field?

- What could I do or make with this?

- How might someone use this information in “the real world”?

Purposeful Practice

Purposeful practice is when you deliberately exercise new skills to improve performance. It requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance (Clear, 2001). This practice will come from assignments provided by your instructor. Be sure to work with your instructor to create a plan to practice new skills to create ownership of your learning.

Learn Online With Laurus College

Laurus College provides quality education and quality experience for people who wish to attain their Bachelor’s and Occupational Associate Degrees. Our commitment to student success goes above and beyond the typical e-learning experience by using our unique “Laurus Learning” program model. Learn more about how online classes work at Laurus College.

Resources

Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bas

Clear, J. (2020, November 11). Deliberate practice: What it is, what it’s not, and how to use it. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://jamesclear.com/deliberate-practice-theory

Crow, G. (2015, February 19). SSDL defining Self-Direction. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from http://longleaf.net/wp/articles-teaching/teaching-learners-text/217-2/

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251-19257.

Flavell, J. H. (1996). Piaget’s Legacy. Psychological Science, 7(4), 200–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00359.x

Forehand, M. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology, 41(4), 47-56.

Lew, D. N. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). Writing to learn: can reflection journals be used to promote self-reflection and learning?. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(4), 519-532.

Settles, B. (2012). Active learning. Synthesis lectures on artificial intelligence and machine learning, 6(1), 1-114.

Song, L., & Hill, J. R. (2007). A conceptual model for understanding self-directed learning in online environments. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(1), 27-42.

Stockdale, S. L., & Brockett, R. G. (2011). Development of the PRO-SDLS: A measure of self-direction in learning based on the personal responsibility orientation model. Adult Education Quarterly, 61(2), 161-180.

Williams, K. C., & Williams, C. C. (2011). Five key ingredients for improving student motivation. Research in Higher Education Journal, 12, 1.

Zull, J. E. (2004). The art of changing the brain. Educational Leadership, 62(1), 68-72.